Breast Cancer Rates: A Paradox of Reduced Deaths but Rising Diagnoses in Young Women

2024-10-10

Author: Jacob

Recent data reveals a disconcerting trend in breast cancer diagnoses among young women in Canada. While mammography has successfully reduced mortality rates from breast cancer by nearly 50% since the 1980s, the number of cases diagnosed in women under 50 has surged significantly. According to the latest reports, breast cancer diagnoses in Canadian women in their 20s have increased by over 45% since 1984. Alarmingly, diagnoses among patients under 50 have risen more than double compared to those aged 50 and above.

In light of these findings, the Quebec Breast Cancer Foundation (QBCF), which proudly marks its 30th anniversary, is advocating for a lower age threshold for breast cancer screening in the province. Currently, Quebec's screening program starts at age 50, allowing women between 50 and 74 to receive mammograms every two years without the need for a referral. However, in contrast, other provinces such as Ontario and Manitoba have begun to lower their screening ages to 40 to enhance early detection.

Dr. Saima Hassan, a surgical oncologist at the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM) and an active collaborator with the QBCF, emphasizes the urgency of revising these age recommendations. "We are facing a situation reminiscent of the pre-screening era, where young women are often diagnosed at more advanced stages of breast cancer," she notes, highlighting the necessity for intensified treatment protocols, including chemotherapy before surgical interventions.

Karin-Iseult Ippersiel, CEO of the QBCF, critiques Quebec's preventive health strategy. "The province operates more on a philosophy of treatment rather than prevention," she declares. As discussions around modifying the screening guidelines are underway, the Quebec Health Ministry has not yet provided a definitive plan regarding these recommendations.

Historically, lack of access to mammography prior to the 1990s resulted in delayed diagnoses and treatment. Since the introduction of the Quebec screening program in 1998, breast cancer death rates have dramatically decreased. However, experts now argue that a multifaceted approach is essential; screening based on individual risk factors—including genetic predispositions, lifestyle choices, and age—is critical, as noted by Dr. Hassan and her QBCF colleague Cédric Baudinet.

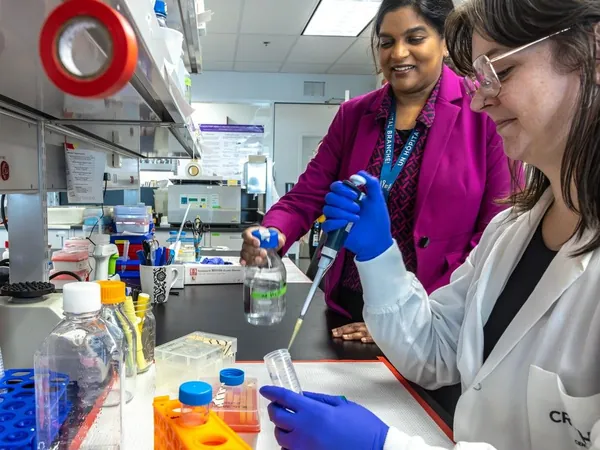

To combat the side effects and discomfort associated with cancer treatments, particularly for young patients who may be reluctant to undergo intensive procedures, Dr. Hassan is spearheading research initiatives. Among these is a promising blood test aimed at assessing the need for mammography, which could streamline detection and improve patient comfort.

Despite varying wait times for screenings—ranging from manageable in Montreal to up to 29 weeks in regions like Gatineau and Abitibi—enhanced access and responsiveness to emerging needs in the health system are integral to tackling these alarming trends in breast cancer diagnoses among young women.

In conclusion, the dual narrative of lower mortality rates and rising incidence in younger populations calls for a reevaluation of current practices and policies towards breast cancer screening. Speedy legislative changes, improved screening protocols, and innovative diagnostic tools are all crucial to safeguarding the health of younger generations against this increasingly prevalent disease.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)