Environmental Concerns Loom as NASA Plans to Deorbit the International Space Station

2024-10-09

Author: Jacob

Environmental Concerns Loom as NASA Plans to Deorbit the International Space Station

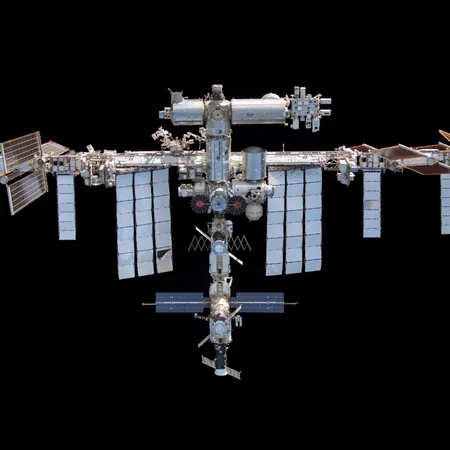

In a bold move that has raised eyebrows and concerns across the scientific community, NASA is gearing up to deorbit the International Space Station (ISS) by early 2031. This monumental task involves safely bringing down over 400 tons of space debris and disposing of it in a specific area of the Pacific Ocean, a proposal that has environmental experts sounding alarms.

The ISS, which has served as a bastion for scientific research since its launch, is now facing critical wear and tear, including cracks and air leaks, according to a recent report from the NASA Office of Inspector General. Faced with these aging issues, NASA has evaluated various decommissioning methods, from returning segments of the ISS to disassembly in space, but has ultimately settled on what many are calling the best-of-bad-options: deorbiting it into a remote ocean site.

NASA has awarded SpaceX a high-stakes contract—worth up to $843 million—to design the United States Deorbit Vehicle (USDV). This craft will utilize a reconfigured Dragon spacecraft equipped with enhanced propulsion systems for a controlled descent aimed at minimizing risks during re-entry. While the vast majority of the ISS is expected to burn up upon re-entry, some denser components may survive to make a splash in the water below.

Enter Point Nemo, ominously known as “the pole of inaccessibility,” where NASA plans to drop these enduring remnants. This site, essentially a graveyard for old satellites and space debris, is strategically located over 1,450 nautical miles from any landmass, ensuring that any surviving debris will likely remain isolated from human populations.

However, this strategy has incited a wave of criticism from environmental advocates and marine scientists. Dr. Edmund Maser, a molecular biologist from Germany, likens the plan to past shortsighted decisions regarding oceanic waste disposal—like dumping munitions from WWII, which have since poisoned the marine ecosystem. "Today, we face the consequences," he cautioned, warning that future generations will bear the brunt of this negligence.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is currently assessing this disposal method, though specific regulations or concerns have yet to be detailed. Ewan Wright, a doctoral candidate at the University of British Columbia, points out that this particular deorbit represents the largest fiery re-entry in history, raising questions about what materials are present on the ISS, and how they could impact marine life.

George Leonard, chief scientist at the Ocean Conservancy, argues that what NASA is planning is akin to tossing single-use plastics into the ocean—an action that shifts the issue out of sight rather than addressing it. Leonard reminds us that pollution has its consequences, and that as humanity continues to rely on the ocean as a dumping ground, we're simply compounding an already dire situation.

Notably, the ISS has played a critical role in advancing scientific research and international cooperation in space. With its impending deorbit, experts assert that it's essential to forge a more sustainable plan for managing space debris and addressing the long-term environmental consequences of our actions—both in the cosmos and on Earth.

As we approach the end of the ISS's storied lifespan, the question remains: can we learn from our past missteps and ensure that our celestial adventures don't lead to environmental repercussions on our home planet? The clock is ticking, and the stakes could not be higher.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)