Is Brain Shrinkage an Indication of Alzheimer’s Therapy Success? New Study Suggests So!

2024-11-25

Author: Emma

Recent research has revealed a surprising perspective on brain volume changes observed in patients undergoing immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease. The findings, led by researchers at University College London (UCL), indicate that the shrinkage of brain volume may actually reflect the effectiveness of the treatment rather than brain cell loss or damage.

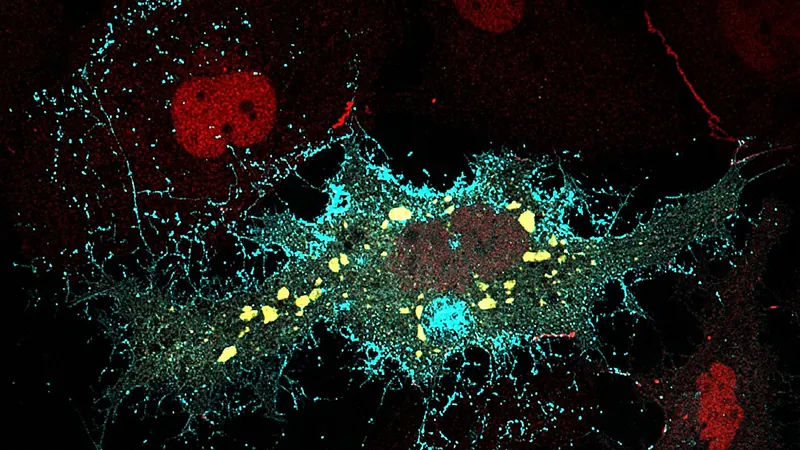

Published in *The Lancet Neurology*, this groundbreaking study analyzed data from a range of clinical trials focused on amyloid-targeting therapies, including the recently approved drug lecanemab by the UK's Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). For individuals with Alzheimer’s, amyloid plaques are harmful accumulations of proteins that disrupt brain function, and their removal has been the core focus of these new immunotherapeutic options.

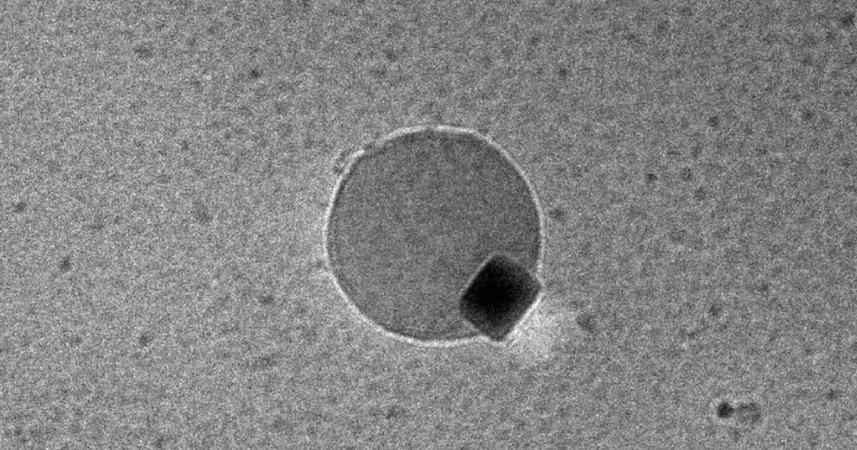

Typically, brain shrinkage is viewed as an undesirable consequence in neurological treatments. However, the UCL researchers found that the extent of this volume loss was similar across various trials and directly correlated with the effectiveness of the therapy in eliminating amyloid plaques. Notably, this reduction in brain volume was not linked to detrimental effects on the brain, leading the team to propose a novel term: "amyloid-removal-related pseudo-atrophy" (ARPA).

Professor Nick Fox, the senior author and director of the UCL Dementia Research Center, emphasized the potential of monoclonal antibodies that target amyloid as transformative in Alzheimer's treatment. He said, "These agents facilitate the removal of amyloid plaques from the brain, which is a significant therapeutic breakthrough." For years, reports of brain volume loss linked to immunotherapy have sparked concerns regarding possible toxicity from these drugs, raising alarm in both public and medical circles.

Despite these fears, the current study argues that the observed brain volume changes are an expected outcome following the removal of pathological amyloid. The researchers are calling for clearer communication and reporting of these findings in clinical trials, particularly as these therapies become more widely implemented.

Lecanemab, which gained approval in August for treating early-stage Alzheimer's in the UK, works by targeting harmful beta-amyloid proteins. This action is considered a key step in mitigating neuronal dysfunction and preventing cell death that characterizes Alzheimer's disease progression.

However, not all reactions to lecanemab have been positive. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has suggested that the benefits of this treatment might not be substantial enough to justify its costs for the NHS. Nevertheless, this ongoing debate about accessibility and effectiveness continues to evolve, with a formal review set to take place after public consultations later this year.

The findings from UCL not only challenge preconceptions about brain shrinkage in Alzheimer's patients but also pave the way for a better understanding of the efficacy of new treatments. This insight could change how the medical community views the effects of anti-amyloid therapies, potentially reshaping the narrative surrounding their safety and effectiveness in combating this devastating disease. With more research needed, it remains imperative to monitor the implications of these therapies as they become integral to Alzheimer's care.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)