Major Setback for Anticoagulant Therapy in Combatting Cognitive Decline from Atrial Fibrillation

2024-11-17

Author: Sophie

Major Setback for Anticoagulant Therapy in Combatting Cognitive Decline from Atrial Fibrillation

CHICAGO -- In a surprising turn of events, researchers have determined that anticoagulant therapy may not be an effective strategy for preventing cognitive impairment in patients with atrial fibrillation (Afib). The findings emerge from the BRAIN-AF trial, which has been halted prematurely due to futility.

The trial indicated that the risk of cognitive decline, stroke, or transient ischemic attack (TIA) was similar between Afib patients with low stroke risk who were treated with lower-dose rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and those who received a placebo. The rates observed were 7% for the rivaroxaban group compared to 6.4% for the placebo group, revealing no significant difference. Notably, the rivaroxaban group also showed a low incidence of major bleeding complications at 0.3%, as opposed to 0.8% for the placebo.

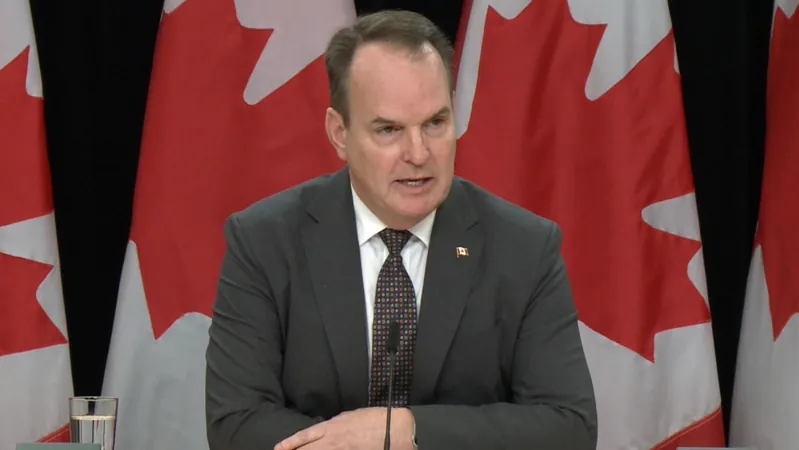

Dr. Lena Rivard from the Montreal Heart Institute presented these results at the American Heart Association (AHA) annual meeting, noting the trial's early termination after a follow-up period averaging 3.7 years vs the planned 5 years.

One of the lingering questions post-trial is the relationship between Afib and cognitive decline. It remains unclear whether Afib directly contributes to cognitive impairment or if both conditions arise due to overlapping risk factors.

Medical experts, including Dr. Andrea Russo from Cooper University Health Care, highlighted that the presence of microemboli, tiny clots that could theoretically travel from the heart to the brain, is just one of several potential explanations for cognitive decline in Afib patients. Russo emphasized the need to investigate other possible mechanisms, such as cerebral hypoperfusion or the impact of medications used to treat Afib.

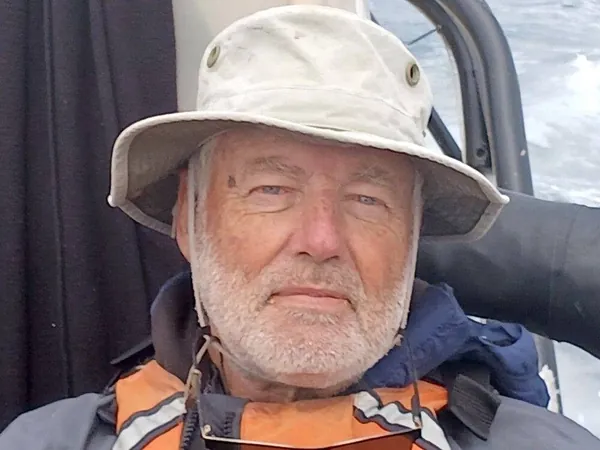

Despite the study's lack of evidence supporting the efficacy of rivaroxaban in preventing cognitive decline, Dr. Hooman Kamel from Weill Cornell Medicine pointed out that the BRAIN-AF trial might not conclusively rule out brain infarcts as a contributing factor to cognitive issues in Afib patients. He noted that the trial's participants were relatively young and healthy, with an average age a little over 53, suggesting that results may not apply to older populations who are often more affected by Afib.

The study included 1,235 Afib patients between the ages of 30 and 62, all of whom had a low risk of stroke as per Canadian guidelines. Notably, the majority of participants were white and only about 25% were women. This demographic limitation, along with the exclusion of individuals with a history of stroke, TIA, hypertension, diabetes, or other bleeding risks, implies that BRAIN-AF's findings may not be applicable to broader, more diverse populations.

Cognitive assessments were conducted at baseline using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), with follow-up assessments yearly. The study defined cognitive decline as a change of 2 points or more drop in the MoCA score from the baseline.

Critically, the study's reliance on the MoCA as the sole measure of cognitive performance was identified as a significant limitation. The findings also apply specifically to the low-dose rivaroxaban used and may not be relevant to other anticoagulants.

In light of these discoveries, experts advocate for future research to prioritize cognitive decline and dementia as key endpoints in clinical trials involving Afib treatments. Dr. Russo asserted that new treatment approaches for Afib should integrate cognitive evaluations from the outset, a sentiment echoed by Dr. Kamel.

As the link between atrial fibrillation and cognitive functions continues to unravel, one thing is certain: emerging treatment strategies must adapt to ensure that they address the full spectrum of challenges that patients face.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)