The Hidden Dangers of Dense Breasts: A Call for Urgent Change in Manitoba's Breast Cancer Screening Policies

2024-09-30

Introduction

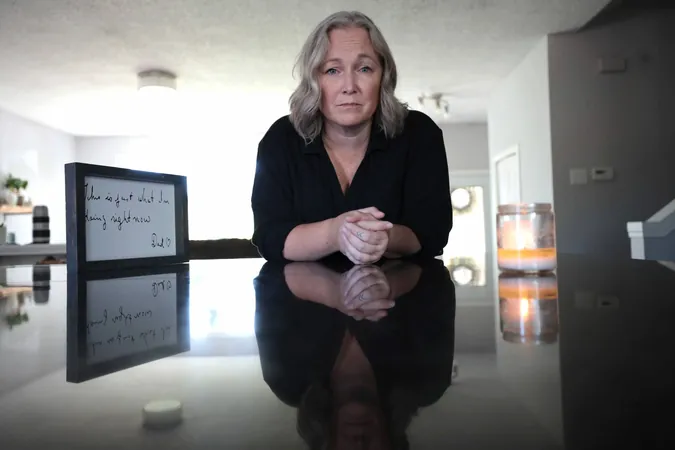

In a heart-wrenching account, Heather Brister, a 48-year-old kindergarten teacher from Neepawa, Manitoba, reveals her struggles with a late breast cancer diagnosis and highlights the lack of adequate breast cancer screening policies in the province.

Brister's Story

Brister’s ordeal began in May 2021 when she discovered a lump, 'the size of a pea,' in her right breast. At that time, being only 44 and lacking any family history of breast cancer, she was deemed ineligible for routine mammography as per Manitoba’s health policies. Instead, after consulting her family doctor, she received a diagnostic mammogram which, to her relief, appeared clear.

However, the relief was short-lived. Eight months later, during recess at school, she felt the lump again—this time it was larger. Despite having a diagnostic mammogram and an ultrasound, the size of the growing mass, which eventually reached nearly 11 centimeters, continued to evade detection, leaving her oncologist to deliver the devastating news that she was facing advanced triple negative breast cancer.

Understanding Breast Density

What Brister—and many like her—did not know is that she had dense breast tissue, a condition that significantly obscures cancerous growths on traditional mammograms. Breast density is classified into four categories, with C and D representing dense breast tissue that can mask tumors. Unfortunately, mammograms often miss cancers in women with these denser breast tissues: up to 40% may go undetected in category D, and about 25% in category C.

According to Jennie Dale, co-founder of Dense Breasts Canada, Brister’s experience is not an isolated incident. Numerous women find out they have breast cancer only after receiving screening results that failed to identify malignancies. 'I have heard so many stories like Heather’s,' Dale says, emphasizing the urgent need for awareness and education around breast density and supplemental screenings.

Current Screening Policies

Manitoba has made some strides in improving awareness; patients are now notified of their breast density in mammogram letters but lack guidance on the implications. As Dale pointed out, while women may be informed of having dense breasts, there are no subsequent recommendations for additional necessary screenings, leaving many in the dark about their risks.

Dr. Paula Gordon, a clinical professor in radiology, asserts that while mammography saves lives, it’s time to rethink breast cancer screening strategies, particularly for women with dense breasts. In British Columbia, for instance, women classified as having dense breast tissue have had access to supplemental screening via ultrasound, drastically enhancing early detection rates.

Personal Accounts

Jennifer Borgfjord, 54, also experienced the pitfalls of the current screening guidelines. After receiving two all-clear mammogram results, she discovered a cancerous lump only weeks later. Despite being informed of her dense breast density, Borgfjord faced delays resulting from missed detections.

Both Brister and Borgfjord emphasize the critical importance of awareness and education about breast density. Both are now actively advocating for policy changes in Manitoba that will empower women, particularly those over 40 with dense breast tissue, to seek supplementary screenings such as ultrasounds or MRIs to ensure timely and accurate diagnoses.

Call for Change

As of recent developments, the provincial government has started plans to increase breast cancer screening accessibility and lower age thresholds for self-referrals for mammograms. However, advocates insist that more vigorous changes must occur.

Brister passionately argues for a system where women can confidently know and communicate their breast density classification, empowering them to demand the screenings they need. 'We must catch it sooner,' she insists, reflecting on her journey and calling on Manitoba to take immediate action to save lives.

In North America, nearly 40% of women over 40 have dense breasts, yet Manitoba’s policies lag behind other provinces where supplemental screenings are offered to those at higher risk. With the consequences of inadequate screening laid bare in personal stories like Brister’s, it’s clear that reform is not just necessary—it’s imperative.

As Brister continues to recover, she hopes for a system that fosters knowledge and proactive health measures, ensuring that no woman has to endure the painful journey she faced. 'Mammograms at age 50 are too late for so many; the age for self-referrals needs to start at 40,' she concludes.

Conclusion

The urgency for change is clear, and the need for awareness is greater than ever.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)