The Nutrition Education Crisis: Why Are Future Physicians Falling Short in Nutritional Competency?

2024-12-30

Author: Emma

Introduction

In a stark reminder of the consequences of poor dietary habits, recent studies reveal that dietary risk factors were linked to a staggering 11 million deaths and 255 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) globally in 2017. Alarmingly, high sodium intake and insufficient consumption of whole grains and fruits topped the list of dietary risks. Experts suggest that a significant percentage of deaths, perhaps one in every five, can be prevented through better dietary practices.

The Role of Nutrition in Preventive Healthcare

The vital role of nutrition in preventive healthcare has been underscored in initiatives such as Healthy People 2010 and its successor, Healthy People 2030. Unfortunately, data shows a concerning drop in the incidence of nutritional counseling during healthcare visits for adults struggling with obesity, falling from 24.8% in 2016 to 21.0% in 2019, falling far below the target of 32.6%.

Medical Trainees' Awareness of Nutrition

The awareness around nutrition's pivotal role among medical trainees is equally compelling. An astonishing 97.6% of first- and second-year medical students at Dalhousie University acknowledged the significance of nutritional counseling in enhancing patient outcomes, and 91.2% believed that physicians hold significant sway over their patients’ eating habits. However, this awareness does not translate effectively into practice, nor is it uniformly supported by medical education.

Perception Among Future Physicians

A study involving internal medicine residents and cardiology fellows from New York University Langone Health highlighted that these future physicians regard nutrition and physical activity as equally essential as statin therapy in curbing cardiovascular disease risks. Yet, a troubling inconsistency remains: the specific role and responsibilities of physicians concerning nutritional care remain unclear. While some practitioners view themselves as primary caretakers in dietary issues, others prefer referring patients to registered dietitians, leading to a fragmented approach to nutritional care.

The Education Gap

Education, or the lack thereof, plays a crucial role in this conundrum. The National Academy of Sciences suggests a baseline of 25 hours of nutrition education within undergraduate medical curricula. However, a national survey showed that 62 to 73% of medical schools in the U.S. fail to meet this recommendation, offering an average of merely 19.6 hours of nutrition instruction—clearly inadequate for aspiring healthcare providers. The Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine (GCSOM) echoed this shortcoming, providing only 14 hours of nutritional training, primarily centered around basic sciences during preclinical phases, which do not adequately address practical applications in patient care.

Global Trends in Nutrition Education

Shockingly, this trend isn’t confined to American institutions; a systematic review spanning numerous countries concluded that nutrition was systematically underrepresented in medical training globally. Students at Dalhousie University, despite recognizing nutrition's importance, largely disagreed with statements regarding the sufficiency of their nutrition education, indicating widespread discontent.

Feelings of Inadequacy Among Medical Students

Survey results from the American Academy of Pediatrics further illuminated this gap, showing that fourth-year medical students felt ill-equipped to meet the nutritional challenges faced by patients, especially in crucial developmental stages like pregnancy and adolescence. These deficiencies in formal training in nutrition critically impede medical professionals' confidence in providing dietary counseling, underscoring an urgent need for comprehensive reforms in medical education to fortify nutrition skills.

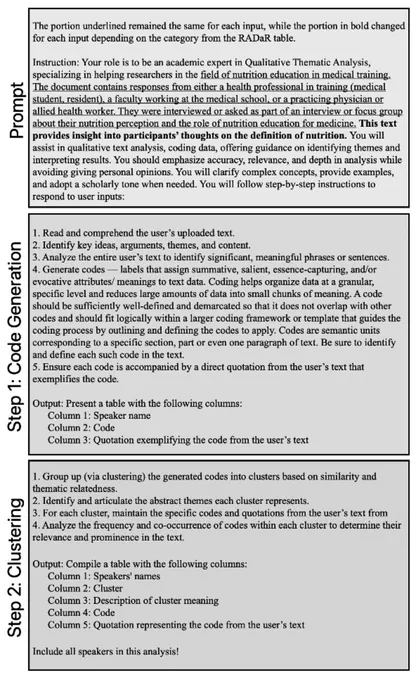

Research Study on Nutritional Competency

This study extensively assessed medical trainees' self-perceived proficiency in nutrition, aiming to discern factors influencing their attitude towards nutrition education at various training levels. A qualitative phenomenological approach guided by social learning theory was employed, exploring how perceptions and experiences shape understanding of nutrition's impact on health.

Survey Results and Insights

Sample participants from various medical backgrounds, including students, faculty, registered dietitians, and nutrition researchers, were engaged in semi-structured interviews, revealing a prevalent sentiment: most healthcare providers believe all physicians should receive nutrition education. Alarmingly, 52.6% of respondents expressed dissatisfaction with their nutrition training, with a gaping distinction noted between nutrition knowledge acquired during medical training versus the substantial amount required to meet patient needs effectively.

Disconnect Between Training and Patient Care

The majority of participants remarked that medical training does not equip them to handle patients' nutritional needs, as many rely on secondhand resources or referrals to dietitians. This defensive approach demonstrates a clear disconnect between theoretical knowledge and practical competency, which poses substantial risks to patient health.

Recommendations for Improvement

Despite this bleak picture, participants suggested numerous opportunities for enhancing nutrition education, advocating for integrated, longitudinal training from medical school through residency. There was consensus that a more holistic approach, possibly incorporating patient-centered strategies and socio-economic considerations, could help bridge the gaps.

Barriers to Effective Nutrition Training

Additionally, participants recognized the barriers constraining nutritional education, including a heavy reliance on standardized exam content, which often sidelines nutrition. This system creates an uninspiring cycle—little incentive to prioritize nutrition education when performance on licensure exams does not demand it.

Conclusion and Call for Change

Our study emphasizes transformative layers needed within medical education and calls for systemic changes to incorporate nutrition more fundamentally in curricula. Legislative reforms, such as the Medical Nutrition Therapy Act, hint at escalating demands for greater nutritional competency among healthcare providers, emphasizing a collective approach that transcends individual efforts.

In conclusion, the necessity for improved nutrition education in medical training has never been clearer. With soaring rates of chronic diseases linked to poor dietary habits, healthcare professionals must be equipped with the knowledge to enact dietary changes for their patients. If we want a healthier future, we must ensure our doctors aren't just knowledgeable about nutrition but are also confident in applying that knowledge practically to significantly alter health outcomes. Time is of the essence, and the call for change is imperative—if we continue to neglect nutrition education, we risk compromising patient care and health outcomes for generations to come.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)