Engineers Revolutionize Heat Transfer with Breakthrough Surface Designs

2025-03-24

Author: Li

In a groundbreaking study, researchers from the University of Texas at Dallas have unveiled a new surface design capable of efficiently collecting and removing condensates, far exceeding their initial predictions based on classical physics. The mechanical engineers were astonished to discover that the new surface gathered more liquid formed by condensation than traditional models anticipated.

This innovative finding exposes limitations in existing theoretical frameworks and has empowered the researchers to introduce a novel theory that elucidates these unexpected results. Published on March 13 in the journal Newton, this new theory is pivotal for enhancing the design of surfaces intended for diverse applications, particularly in water harvesting from atmospheric moisture without the need for electrical energy.

Dr. Xianming (Simon) Dai, the lead author and an associate professor of mechanical engineering in the Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Science, emphasized the significance of their research. “This new theory will enable us to design surfaces that optimize the condensation process, improving efficiency in various technologies,” he stated.

Dai's research spans multiple applications, including effective water harvesting techniques and advancements in refrigeration systems. His overarching goal is to create surfaces that not only collect but also rapidly eliminate condensed droplets, ensuring continuous condensation processes.

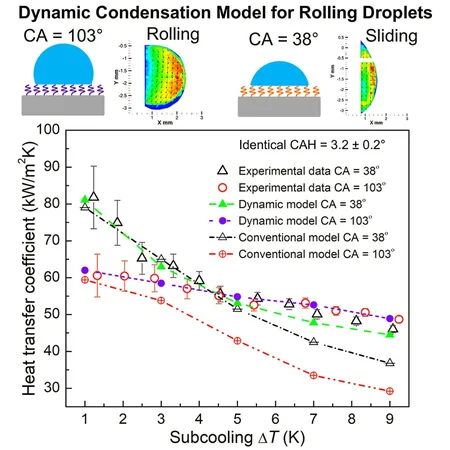

The core of the researchers' novel theory focuses on the behavior of rolling droplets during dropwise condensation, a phenomenon where vapor converts into tiny liquid droplets on a surface. This mode of condensation is advantageous as it allows droplets to roll off, clearing the surface for further condensation, thereby maximizing water collection capabilities.

Deepak Monga, a Ph.D. candidate in Dai's lab, made a remarkable observation regarding the new surface design: certain areas were devoid of visible droplets, a scenario that classical theories had not accounted for. Upon deeper investigation, the team found that those "invisible" areas significantly contributed to condensation, highlighting a flaw in the half-century-old theoretical model. The droplets in these regions, although unseen, were in the early stages of formation, revealing that the classical model overlooked the rapid speed at which the new surface could both collect and shed condensates.

“It’s all about speed. The classical heat transfer theory does not consider the rapid removal of condensates our new surface facilitates,” Monga explained. “In our revised model, we included a parameter for disappearing frequency to account for this high-speed rolling phenomenon.”

Under the guidance of Dr. Yaqing Jin, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering, the team conducted meticulous experiments to measure and visualize the behavior of micrometer-sized water droplets. By employing an advanced time-resolved particle image velocimetry system paired with a sophisticated long-distance microscope, they could capture the flow dynamics and movement of these tiny droplets on the surface.

“The system boasts extraordinarily high resolution, enabling us to observe flow velocities and the distribution of droplets, thus enhancing our understanding of how these droplets interact with the surface,” Jin noted.

Building on their new theory, Monga has already applied it to craft an innovative surface, which he showcased at the American Society of Mechanical Engineers' 2024 Summer Heat Transfer Conference, where his presentation received accolades for best presentation.

This revolutionary research not only enhances our comprehension of heat and mass transfer but also promises to impact sustainable technology significantly, ensuring smarter solutions for water collection in the era of climate change. Stay tuned as we follow the ongoing developments in this exciting field!

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)