Shocking Truth Revealed: Microplastics Could Linger in Your Body Longer Than You Think!

2024-10-09

Author: Jia

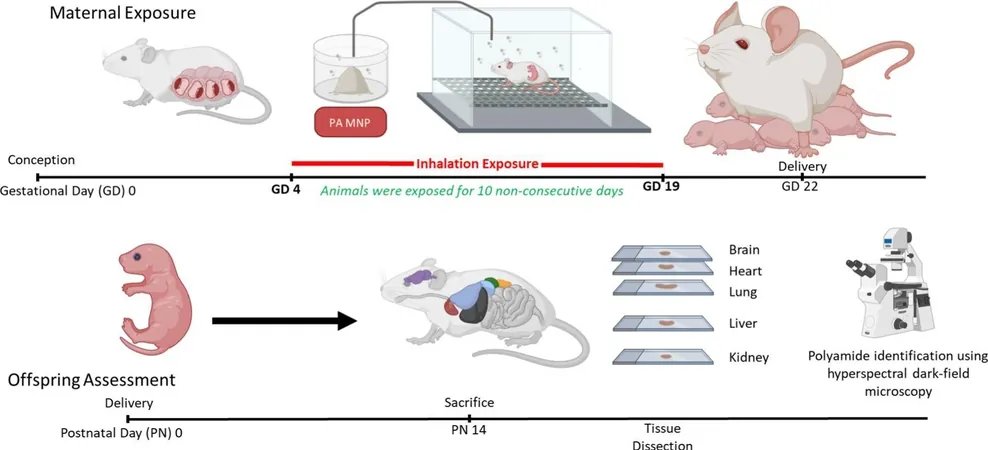

Plastic pollution isn't just an environmental crisis; it's infiltrating our very bodies! A groundbreaking study by researchers at Rutgers Health, published in the journal *Science of The Total Environment*, has found tiny bits of plastic, known as micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) — smaller than a grain of sand — present not only in the environment but also in the tissues of newborn rodents.

For years, we've understood that these microscopic pollutants enter our bodies through inhalation, absorption, and dietary sources. Alarmingly, they can even cross the placental barrier during pregnancy, depositing harmful particles into fetal tissues. This new research, however, reveals a persistent problem: once these plastics enter the body, they may not go away after birth!

In a compelling experiment, the researchers exposed pregnant rats to aerosolized food-grade plastic powder for ten days. The results are unsettling: two weeks after giving birth, both a male and female rat exhibited the same type of plastic found in their mothers' bodies across various organs, including the lungs, liver, kidneys, heart, and even the brain! In stark contrast, the control group showed no traces of plastic.

Phoebe A. Stapleton, the study's senior author and an associate professor of pharmacology and toxicology, articulated the gravity of the findings. "Nobody wants plastic in their liver,” Stapleton expressed. "Now that we know it’s there—along with other organs—the next stage is to decipher the ‘why’ and the implications for health."

As these micro- and nanoplastics invade every facet of our planet—from farmland to the deepest oceans—stakes are rising. Evidence continues to mount linking these pollutants to severe health issues including cancer, immune dysfunction, inflammation, and cardiovascular diseases. It is becoming increasingly clear that these invisible invaders may be placing our health at risk and threatening maternal-fetal health.

The pressing question now is: What can policymakers do? Stapleton hopes her findings catalyze a sense of urgency among decision-makers, emphasizing the need for increased funding and research. “Without answers, we can’t have policy change,” she warned.

Although completely eradicating plastics seems unrealistic given their importance in modern life, there is hope for future regulations. The research suggests that informed policies could guide the production and use of less toxic plastic substances, which could potentially mitigate health risks associated with plastic exposure.

As we keep uncovering the mysteries surrounding microplastics, understanding their long-term impact on human health will be crucial for implementing protective measures. Stay tuned, because as more studies emerge, this story may only be just beginning. Will our world ever be plastic-free, or will we learn to navigate a future riddled with invisible threats?

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)