Unraveling Relentless Malaria Transmissions: The Enigma of Anopheles funestus in Zambia

2024-10-14

Author: Mei

Malaria is one of the most daunting public health challenges, and while significant strides were made in controlling the disease through insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) from 2000 to 2015, this progress appears to have plateaued. Alarm bells are ringing in the malaria community as high levels of transmission persist despite the global adoption of vector control measures. A recent study sheds light on the perplexing situation in Zambia's Western Province, where Anopheles funestus, the primary malaria vector, continues to thrive and propagate the disease, even with robust adherence to control strategies.

A Stagnant Struggle Against Malaria

The stagnation in malaria control can be attributed to a multitude of factors that may vary across regions. Contributing elements include insecticide resistance, evolving vectors, underfunded control programs, and even societal issues like conflict and population displacement. This situation calls for urgent, localized data to understand why malaria transmission remains high, despite the implementation of established best practices in vector management and treatment protocols.

A pivotal phase III trial conducted in Western Zambia aimed to evaluate the use of Attractive Targeted Sugar Bait (ATSB) stations, a promising new intervention, alongside ITNs and Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS). Remarkably, the study revealed minimal impact on both clinical cases and malaria-carrying mosquito populations, even in a region with seemingly adequate vector control coverage. Despite more than 70% of residents sleeping under ITNs and numerous households receiving IRS treatment, a resilient wave of malaria transmission prevailed.

Understanding Residual Malaria Transmission

The World Health Organization defines residual malaria transmission as persistent cases that remain following effective prevention measures. This residual transmission doesn’t necessarily indicate that the vectors are developing resistance; it can also arise from behaviors that evade control strategies. For instance, Anopheles funestus is known for its preference for human blood and demonstrates outdoor biting behaviors that occur when people are unprotected.

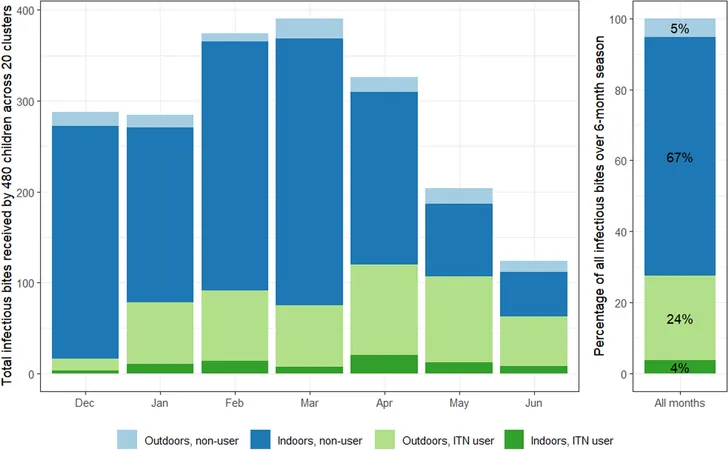

In Zambia's Western Province, outdoor biting is an escalating concern. Recent evidence indicates that more bites are occurring outdoors after dusk, which could significantly contribute to the sustained malaria transmission rate. It’s estimated that just a 10% uptick in outdoor biting could increase the entomological inoculation rate (EIR)—the average number of mosquito bites that transmit malaria—by nearly 0.46 infectious bites per person each year.

The Impact of Behaviors on Transmission Dynamics

A comprehensive analysis of mosquito behavior and human interactions has become essential in measuring the persistent malaria transmission risk. An elaborate methodology combining human landing catches—where researchers collect mosquitoes that land on exposed individuals—and observed human behavior patterns has been employed to derive a more nuanced understanding of exposure levels.

In a shocking revelation, data indicated that nighttime biting levels variable across clusters, as well as resistance patterns among mosquito populations, create an unpredictable malaria risk landscape. While higher EIR rates were measured in children who didn’t use ITNs, even ITN users still faced a significant risk of exposure, as many bites were recorded when children were outside at night.

A Call for New Strategies

This alarming persistence of malaria transmission emphasizes that current control measures, while effective to an extent, may not be enough. Given that approximately 90% of bites in this area could be prevented with optimal ITN use, it signifies the urgent need for multidisciplinary strategies that address not just vector control but also human behavior and ecological dynamics affecting malaria transmission.

Future initiatives could involve deploying next-generation insecticides, refining public health messaging to encourage better adherence to ITN usage, and focusing on outdoor biting awareness. Furthermore, active engagement with communities to educate them about the importance of protective measures during outdoor activities in the evening and early morning could play a critical role in curbing malaria resurgence.

Conclusion: No Room for Complacency

As we confront the realities of malaria in the 21st century, complacency is a luxury we cannot afford. The findings underscored in this study bring to light the complexities enveloping malaria transmission in Zambia, urging a re-evaluation of present methods and a call for innovative solutions. As we enhance our understanding of Anopheles funestus behaviors alongside human interactions, we may yet find the tools necessary to reclaim the gains in malaria control that have been hard-fought but remain precariously balanced on the edge of ongoing transmission threats.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)