Unraveling the Connection Between Gestational Insulin Resistance and Postpartum Depression

2024-10-08

Author: Mei

Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a severe mental health condition that impacts approximately 17% of new mothers globally, translating to nearly one in five pregnancies. The underlying causes of PPD are still under investigation, but a multitude of factors, including genetics, hormonal fluctuations, and environmental stressors, are believed to contribute to its onset.

The Insulin Connection

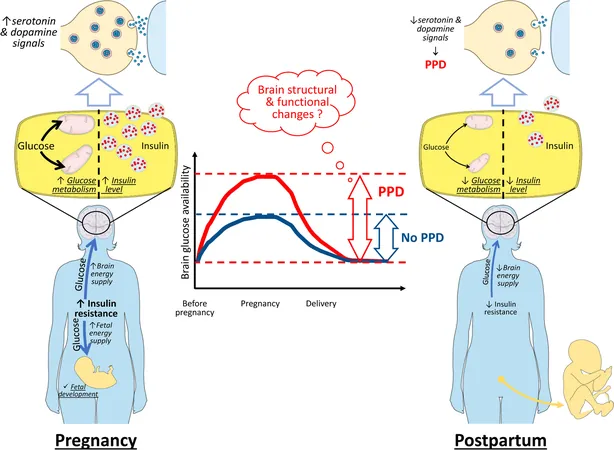

Recent studies have unveiled a concerning link between gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and the risk of developing PPD, primarily through the lens of insulin resistance (IR). During pregnancy, IR serves as a natural mechanism to ensure glucose availability, meeting the metabolic demands of both the mother and developing fetus. However, the rapid resolution of IR following childbirth may disrupt the metabolic balance of both peripheral tissues and the brain, potentially paving the way for PPD.

Emerging hypotheses suggest that changes in how the body processes glucose and insulin postpartum could have significant ramifications for mood regulation. Insulin and glucose play crucial roles in brain function by modulating neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin, chemicals vital for mood stabilization. A sudden postpartum drop in insulin and glucose levels may lead to mood swings and depressive symptoms characteristic of PPD.

The Impact of Hormonal Changes

Hormonal fluctuations during and after pregnancy are critical factors implicated in PPD. The significant rise in hormones like estrogen and progesterone during gestation, followed by a steep decline postpartum, can lead to mood disturbances. Additionally, thyroid hormones, cortisol, and oxytocin may also play roles, yet the exact contributions of these hormones to PPD remain unclear.

GDM may exacerbate the risk of PPD due to the pronounced metabolic changes experienced by these mothers. Research has shown that individuals diagnosed with GDM demonstrate a 1.59-fold increase in their likelihood of experiencing PPD, suggesting that the metabolic disruptions tied to IR pose unique risks.

Understanding Brain Metabolism

The brain requires an enormous amount of energy—consuming nearly 20% of the body's total energy despite its small mass. Historically thought to rely solely on insulin-independent glucose transport methods, recent findings indicate that the brain also utilizes insulin-dependent pathways. Insulin levels in the brain can be derived from peripheral sources but can also be synthesized by neurons, further complicating the relationship between metabolism and mood.

Studies have revealed that glucose administration boosts brain function in experiments, leading to enhanced memory and improved mood in clinical settings. The targeted brain regions affected by insulin include those critical for mood regulation, such as the nucleus accumbens and amygdala. Disruption of this insulin-glucose balance can lead to mood disorders, including PPD.

The Mechanisms Behind PPD Development

After childbirth, the transition from gestational IR back to normal can potentially disrupt the neural pathways that govern mood. For women with GDM, who experience larger swings in IR and metabolic activity after delivery, these disturbances could be more pronounced, heightening the risk of developing PPD.

Although many risk factors for PPD exist—from hormonal fluctuations to stress and changes in sleep patterns—there remains a need for deeper research into the specific role of IR and glucose metabolism in its onset. The concept that PPD may stem from the abrupt changes in insulin and glucose levels postpartum offers a novel perspective that warrants further investigation.

Conclusion

The relationship between postpartum depression and gestational insulin resistance is a developing field of study presenting valuable potential for future preventative strategies. If corroborated, these findings could pave the way for tailored interventions that manage insulin and glucose levels in new mothers, improving outcomes for both maternal mental health and infant care. As we advance our understanding, it is clear that both metabolic health and mental well-being are inextricably linked, prompting a more holistic approach to postpartum care.

Future research is paramount, not only to establish these connections but also to provide insights that could transform how we understand and manage postpartum depression, revealing the intricate dance between our body’s metabolism and our mental health.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)