Revolutionary Study Unveils Surprising Flexibility of Birds in Urban Habitats!

2024-11-07

Author: Michael

As the world faces a concerning decline in bird populations, researchers from the University of Vermont have uncovered a groundbreaking perspective on how some species demonstrate remarkable adaptability to habitat changes. This new study opens the door to innovative strategies for urban gardening and city planting initiatives that could bolster avian populations.

Published in the Journal of Animal Ecology, this study comes at a time when data shows Canada and the United States have lost nearly three billion birds over the past 50 years. The challenge lies in accurately tracking these populations, particularly due to the absence of long-term data that highlights changes over time.

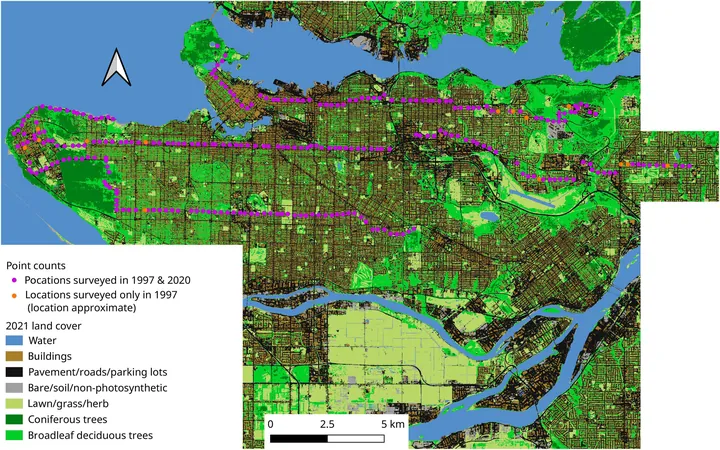

In their research, Harold Eyster, a climate scientist at the Nature Conservancy and lead author of the study, utilized extensive datasets from bird surveys conducted in the Vancouver metro area spanning from 1997 to 2020. These datasets included land cover changes analyzed through advanced techniques such as satellite imagery and machine learning.

The data revealed a staggering 26% overall decline in bird populations, with house sparrows, barn swallows, and starlings facing reductions as severe as 80-90%. However, the study suggests that factors beyond land cover changes may be at play. Eyster notes, “Our findings indicate that existing ecological models might be overly simplistic, misrepresenting the strength of the connection between habitats and bird populations.”

Notably, birds are resilient creatures. The research showed that by 2020, certain species like chickadees and bushtits have significantly increased in population, demonstrating a potential shift in ecological dynamics that challenges traditional bird conservation approaches.

The study emphasizes the complexity of ecological systems, as Brian Beckage, a professor involved in the research, explained. "When you analyze data from a single time point, you miss a lot of underlying trends affecting wildlife." He advocates for longitudinal studies to better understand these intricate relationships and develop effective strategies for wildlife conservation.

Furthermore, urban environments seem to offer unforeseen benefits for birds. Eyster and Beckage's previous research suggests that planting coniferous trees not only cools metropolitan areas during heat waves, benefiting both humans and birds, but it also enhances the overall urban landscape. As cities house more than half the global population, they present invaluable opportunities for fostering harmonious interactions between humans and wildlife.

Remarkably, Eyster discovered that some bird species, like the Pacific Wren, exhibit a more adaptable behavior than previously recognized. While these birds typically nest in large forested areas, they have begun to exploit urban spaces during non-breeding months, venturing into yards and gardens. This adaptability indicates that urban planners might need to rethink conservation strategies, considering not only large parks but also the smaller natural patches within residential areas.

While climate change is often positioned as the sole villain in wildlife decline, the findings suggest that habitat loss, food supply alterations, and increased competition must all be examined. Eyster explains that disentangling these factors is crucial for understanding how to support declining bird populations effectively.

In conclusion, as researchers strive to unravel the complexities behind avian declines, the urban landscape emerges as a crucial battleground. By fostering environments that accommodate adaptable species, we can transform our cities into thriving ecosystems for birds and create a revitalized connection between wildlife and urban dwellers. The resilience of birds may indeed shine a light on innovative conservation solutions that could reverse troubling trends in bird populations worldwide.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)