Unveiling Ancient Diets: The Secrets of Stone Cooking Tools

2025-04-07

Author: Michael

In a groundbreaking study, researchers at the Natural History Museum of Utah have delved into the mysteries held within ancient stone cooking tools, offering a fascinating glimpse into the diets of our ancestors.

Imagine your modern kitchen, equipped with a mortar and pestle or a cutting board. These everyday items are descendants of the ancient manos and metates—stone instruments that have shaped the culinary practices of civilizations for eons. A mano is a handheld stone tool used alongside a metate, a large stone surface used for grinding food materials derived from both plants and animals. Archaeological findings indicate that these bedrock metates date back as far as 15,500 years and are widespread across various sites.

Employing innovative techniques, researchers are extracting minute plant residues from the surfaces of these metates to explore the historical significance of the foods processed in them. This study is detailed in the reputable journal American Antiquity.

According to archaeobotanist Stefania Wilks, who is part of this ambitious research project, “People have lived here for time immemorial and have been processing native plants on ground stone tools for a long time.” Her focus is on analyzing how traditional food and medicinal plants have shaped lifeways and influenced local landscapes in the Western U.S.

Wilks collaborates with Lisbeth Louderback, the NHMU’s Curator of Archaeology, to sift through ancient metates scattered throughout Western North America. They concentrate on starch granules—tiny carbohydrate structures that play an essential role in plants' energy storage. Despite their reduced size, these granules could reveal vital insights about the nutritional practices of ancient cultures.

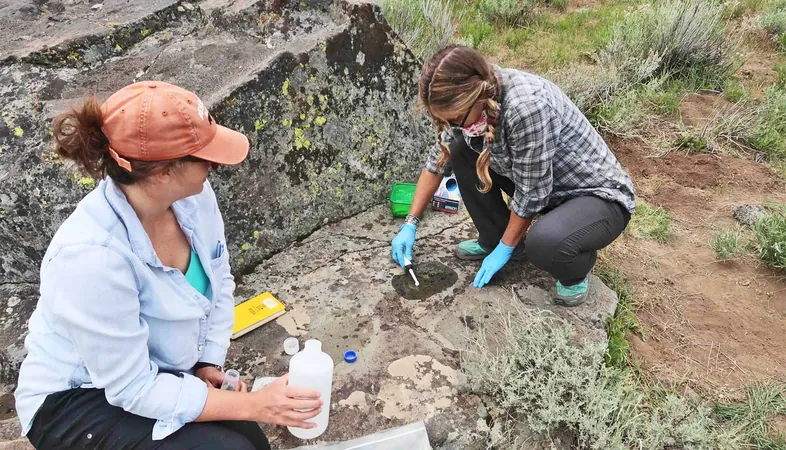

The extraction process demands meticulous attention, as these starch granules are too small to be observed with the naked eye. The researchers extract them from stone surfaces where ancient processing activities took place. Wilks and Louderback were particularly intrigued by the bedrock metates; although seemingly exposed to degrading elements, they speculated that crevices could protect hidden plant residues.

“Through their actions of grinding and mashing, people would have forced these starches down deeper into the stone,” Wilks explained, emphasizing the intricate relationship between human activity and the preservation of these microscopic remnants.

The appearance of bedrock metates can range widely, influenced by the type of rock used. In Utah, for instance, the prevalent sandstone forms elongated grooves, while other locations may reveal circular or dish-shaped metates. Despite lacking the allure of artifacts like arrowheads, Wilks argues that these stones are treasure troves of historical information regarding ancient food practices.

In southern Oregon, for example, numerous bedrock metates align along basalt outcrops, interconnected with shadowy ancient petroglyphs and crucial plant populations, including geophytes, known for their starchy roots and tubers. Previously, archaeologists believed these uplands were primarily used for hunting; however, this research has begun to reveal their role in plant processing as well.

The painstaking process to analyze these metates involved cleaning their surfaces to gather plant residues, then comparing those particles embedded in the metate’s crevices. Using electric toothbrushes and deflocculants, the team successfully isolated deeply lodged starch granules for inspection.

The results were remarkable: while the surface yielded few granules, the samples from deeper within the stone revealed hundreds, providing strong evidence of intense plant processing activities.

Further analysis allowed the researchers to identify various plant species associated with the starch granules. They discovered a prominent presence of the carrot family, including the biscuit root—a vital food source for Indigenous cultures—along with wild rye and lily family plants. This information is crucial as starch analysis can fill knowledge gaps in traditional diets, especially since certain plant parts decompose quickly and leave little trace.

Wilks remarked, "Starch analysis is beneficial because various food plants do not preserve well in the archaeological record—unearthing these granules gives us profound insight into ancient diets."

This innovative method of studying ancient dietary practices through starch extraction not only enriches our understanding of human health and nutrition throughout history, but it also emphasizes the importance of often-overlooked artifacts like bedrock metates in archaeology. As we continue to unveil these ancient food secrets, we gather invaluable knowledge about how our ancestors lived, thrived, and adapted to their environments.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)