Could Mouse Sperm Circling Earth Hold the Key to Humanity's Survival?

2024-12-16

Author: Yu

Introduction

In recent years, humanity has faced unprecedented challenges, from global pandemics to record-breaking heatwaves and natural disasters. These events underscore the urgent need for humans to seek alternative living environments beyond Earth. Visionaries argue that establishing outposts on the Moon or Mars could serve as a safeguard against extinction due to catastrophic events or self-destructive behaviors.

The Mystery of Reproduction in Space

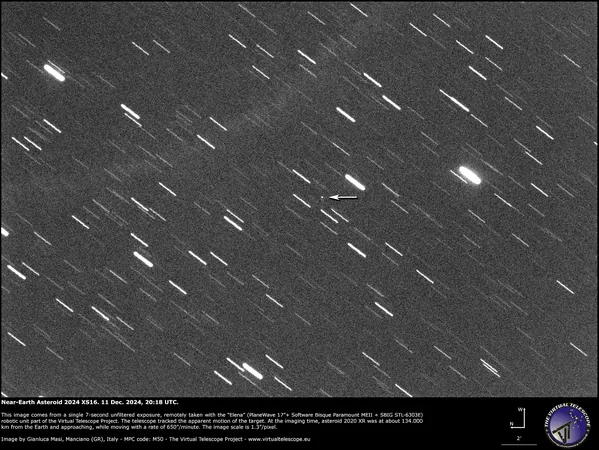

However, one of the biggest mysteries remains: Can we reproduce in space? Recent experiments involving freeze-dried mouse sperm, currently housed aboard the International Space Station (ISS), aim to provide insights into the reproductive capabilities of mammals beyond our home planet. These specimens are set to return to Earth next year, where Teruhiko Wakayama, a professor at the University of Yamanashi’s Advanced Biotechnology Centre in Japan, will examine the effects of the space environment on these gametes and their potential for generating healthy offspring.

Wakayama's groundbreaking research includes the development of a device allowing astronauts to perform in vitro fertilization (IVF) with rodents on the ISS in the near future. 'Our aim is to establish a reliable system for preserving Earth's genetic resources in space,' he states, emphasizing the potential for life to be revived even if Earth were to face dire circumstances.

Wakayama's Contributions to Reproductive Science

The concept may sound like something straight out of a science fiction film, but Wakayama has been at the forefront of reproductive science for decades. He was instrumental in pioneering techniques to clone the first mouse from adult cells in 1997, and he led studies on mouse embryo development in space—a feat previously only achieved with amphibians and fish. His innovative freeze-drying method allowed mouse sperm to be sent to the ISS, where it remained viable in a freezer for up to six years. Researchers have successfully rehydrated the samples to produce healthy baby mice upon their return.

Wakayama's current experiments could extend the potential viability of freeze-dried sperm in space up to 200 years, but he acknowledges this is insufficient for the long-term survival of a human colony. He is now working to protect sperm stored at room temperature from harmful radiation, exploring the possibility of indefinite storage in space.

Exploring Reproduction in Space: Past Experiments and Future Prospects

Space agencies have a history of launching terrestrial organisms into space to investigate the effects of microgravity and cosmic radiation on biological processes, including reproduction. Notably, in 1989, a batch of fertilized chicken eggs labeled 'Chix in Space' was sent into orbit as part of an experiment sponsored by KFC to study their development in zero gravity.

In 1992, the Space Shuttle Endeavour became home to tadpoles that were the first vertebrates to experience their early life stages in microgravity, illustrating the challenges faced in seeking air bubbles to breathe. Other experiments include the 2007 birth of cockroaches in orbit, offering further insights into the adaptability of life in extreme conditions.

Dr. Virginia Wotring from the International Space University notes that while recent experiments show some species can reproduce in space, understanding mammalian reproduction in microgravity is crucial. She highlights successful reproduction cycles observed in aquatic creatures, paving the way for future studies with mammals like mice.

Challenges Ahead

With mouse sperm returning to Earth in 2025, Wakayama cautions that while the ultimate goal is to permanently preserve reproductive cells in space, the challenges are significant. He emphasizes the necessity of addressing the needs of astronauts, who confront immediate medical risks from cosmic radiation and microgravity's effects on human physiology, including muscle and bone loss.

Importantly, his upcoming research could unravel whether fertilized embryos can develop properly in microgravity, where conventional principles of gravity do not apply. 'We don't yet know how vital biological processes will function under these conditions,' he elucidates.

Conclusion

As efforts to establish a human presence on other planets progress—like NASA's Artemis program, which aims to return astronauts to the Moon by 2026, and SpaceX's anticipated crewed mission to Mars—scientific inquiries, such as Wakayama's, will be paramount in determining not only the feasibility of human reproduction in outer space but also the broader implications for continuing civilization beyond Earth.

For Wakayama, the stakes couldn't be higher. 'If we can confirm that human life can thrive in space, it would offer invaluable reassurance. However, if challenges arise, we must understand how to confront those obstacles,' he concludes. Only time will tell if mouse sperm in orbit might indeed pave the way for the future of humanity beyond the stars.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)