New Study Debunks Myth: Mexican Free-Tailed Bats Are Not Major Carriers of Chagas Disease in Texas

2024-10-02

New Study Debunks Myth: Mexican Free-Tailed Bats Are Not Major Carriers of Chagas Disease in Texas

A groundbreaking study from Texas A&M University is shaking up common misconceptions about the role of bats in disease transmission. While bats are often associated with various zoonotic diseases, this research highlights that Mexican free-tailed bats are unlikely to be significant carriers of Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi), the parasite responsible for Chagas disease.

Published in the Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports, the study set out to clarify the relationship between these bats and the transmission of Chagas disease in the Lone Star State. 'Bats are often seen as the original hosts for T. cruzi, especially since they roost in close proximity to human households,' explained Ilana Mosley, a PhD student in Veterinary Integrative Biosciences at Texas A&M. 'That proximity raised questions about their potential role in spreading this disease, necessitating this investigation.'

Chagas disease is infamous for its sneaky symptoms, which can easily mimic other conditions, leading to heart failure or even cardiac arrest. Its primary transmission vector is the infamous 'kissing bug,' which spreads the parasite through its feces after feeding on the blood of animals and humans.

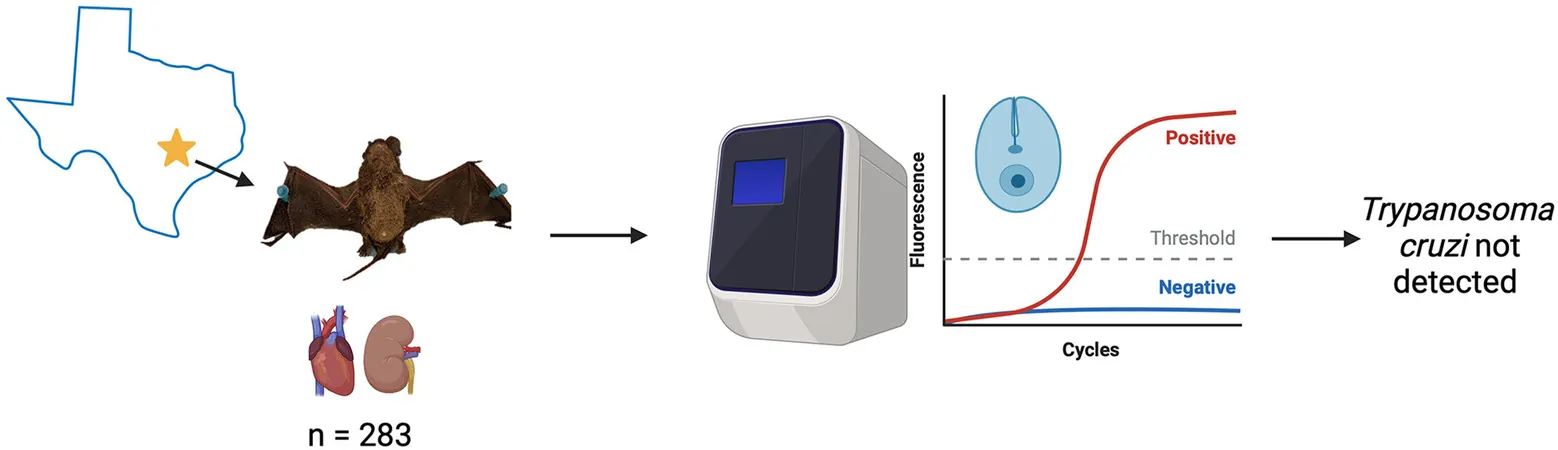

Mosley's study involved testing around 300 local Mexican free-tailed bats, all of which yielded negative results for T. cruzi. 'While it’s possible we could have missed the parasite, such a substantial sample size suggests otherwise,' Mosley remarked.

The implications are significant for Texas residents. Dr. Sarah Hamer, a co-author of the study, reassured, 'The results indicate that having Mexican free-tailed bats roosting near your home shouldn't elevate your risk for Chagas disease. However, vigilance remains essential regarding kissing bugs, which continue to pose a real threat.'

This unexpected shift in understanding also raises new questions about bat behavior. Despite being insectivores, why aren't these bats consuming kissing bugs, which are a known host for the disease? The findings present an intriguing puzzle for future research.

An unexpected opportunity for this study arose during Winter Storm Uri in February 2021 when severe weather left many Texas residents in the dark and took a toll on wildlife. Hundreds of Mexican free-tailed bats fell victim to the cold and food scarcity, allowing researchers to collect data that would not have been possible under normal circumstances.

'While it was tragic to see that happen, it provided us a unique opportunity to study a large volume of specimens,' commented Hamer. Unlike prior studies that relied on small blood samples from live bats, the unfortunate context allowed for thorough testing of organs and larger amounts of blood. This methodology is crucial to accurately detect T. cruzi, as the parasite can hide in various tissues after infection.

The research team did not stop at studying the bats—they also collected samples from fleas and ticks associated with them, and the remains have been donated to a natural history collection at Texas A&M for future research. As Dr. Jessica Light, a curator at the university, emphasized, the preservation of these specimens is vital for ongoing studies and could lead to new discoveries in the field of parasitology.

So, while Texas residents can breathe a little easier knowing that their local Mexican free-tailed bats are not playing a major role in the spread of Chagas disease, the study prompts further inquiry into the relationship between these bats, kissing bugs, and the diseases they might transmit. Keep an eye on this evolving narrative—who knows what the next set of findings will uncover!

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)